A dapting the true story of a war reporter in Afghanistan may seem like a left field project for Robert Carlock, who is best known for his work on FRIENDS, SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, 30 ROCK and UNBREAKABLE KIMMY SCHMIDT, but WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT (Paramount Pictures) is as fearless and captivating as anything he’s ever written.

dapting the true story of a war reporter in Afghanistan may seem like a left field project for Robert Carlock, who is best known for his work on FRIENDS, SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, 30 ROCK and UNBREAKABLE KIMMY SCHMIDT, but WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT (Paramount Pictures) is as fearless and captivating as anything he’s ever written.

Based on journalist Kim Barker’s memoirs, WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT is an examination of what it’s like to be a war correspondent covering an ongoing conflict that America has tuned out. Robert’s script brings light to the passion and sacrifice made by journalists and soldiers and how they use humor to make sense of it all.

The WGAE spoke with Robert about writing his first adapted screenplay, his writing process and how working on a feature film differs from working on a television series.

How did you get your first break as a writer?

I got my start thanks to Louis C.K., who was the head writer of the kind-of mythical THE DANA CARVEY SHOW. I had a sketch packet that had somehow found its way to him and he liked one of my sketches. One of the six. I think they had some money lying around over there, so I went to New York. That was my first job. I shared an office with John Glaser and Charlie Kaufman. Steve Carell and Stephen Colbert were down the hall. Dana, Robert Smigel, Louis, Heather Morgan, Bill Cotton. All these amazing people. Three months later, I was – we were – out of a job. That was a good first lesson in the industry: It doesn’t matter how you have it lined up. Some things are out of your control.

How did the WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT project come to you?

I’ve worked with Tina [Fey] for a while, to my great benefit. She or her producer, Eric Gurian, had read a review of Kim Barker’s book, The Taliban Shuffle: Strange Days In Afghanistan and Pakistan. That’s where they got the source material for the movie. In a review, Kim was described as a Liz Lemon / Tina Fey character. That caught her attention. They then went and bought the book. It seemed interesting to have Tina play a war correspondent. She brought it to me and I readily agreed with her that it’s a fascinating, funny, weird, harrowing book. It felt like a fun and challenging change of pace for us both. I’ve always been interested in the world there in Kabul and said “Yes” immediately to try to turn it into a movie.

What was your process for adapting The Taliban Shuffle?

This is my first adaptation. We won’t say, “First and last.” The book is wonderful, but it doesn’t tell a story in the way that I think a movie needs to be told. It was a well-written book with clear emotional arcs of this woman. You trace an arc and say, “Okay, now what parts of this book help tell that story?”

Again, it’s a memoir and it’s a series of great stories and incredible characters in a deeply rich and dense world. In one-hundred and fifty minutes, you don’t have all the luxuries of a book. You need to have a narrative. There is a narrative in the book, it’s just very internal, so it’s a process of taking away and adding and extrapolating. I had to figure out what are the things that can help dramatize Kim’s internal journey. Because of the nature of the world there, it’s pretty intense and interesting, not to mention cinematic and visual.

It’s the first time I’ve written anything where the people can get shot. We’re talking about the real world and it’s nothing to take lightly. Those are big stakes. That’s a good demonstration of courage under fire. It’s a good demonstration of, “Maybe this woman can do it here.”

There is that great scene early in the film where Kim is embedded with soldiers as they come under fire and she puts herself in a bit of danger for the sake of her story. Are there specific moments like that in the book that you wanted to capture in the script and see on screen?

There definitely were. When Kim goes to Kandahar in the south of Afghanistan. Kandahar was a Taliban stronghold and becoming less and less stable and safe. In the book, in order to travel more easily and not be so obvious as a Westerner, Kim wears a ruffled burka. That immediately jumped off the page. How visual it was. Not to mention, what it says to put Tina Fey in a burka. There were moments throughout the book like that, where it felt like that has to be part of the movie. That’s so much what the book is about and what I wanted the movie to be about.

What were your source materials outside of the book? Did you talk with Kim about the project? Did you look at articles from around that time?

I spoke with Kim quite a bit. In our first meeting, which was a bit nerve-wracking, I knew I needed to ensure her that I was taking this very seriously. Not knowing her, I had to introduce an idea that she may not have fully internalized, which is that I was going to take her life and change things. I’m going to combine people. I’m going to compress time. I’m going to add narrative elements that I hope are representative of her experience. Before I could get into that difficult conversation, she preempted. She is a very smart lady and was very aware of what she wrote and what movies are.

That led to a very helpful collaboration in terms of getting stories from her that weren’t in the book that helped me understand her world. I spoke to a number of her friends. They led me to other friends. That always would lead to various books and articles. I spent a fair amount of time reading the news from 2003 to 2006.

It was daunting to try to — even with the book as a foundation – write about the news, in particular, foreign correspondents. To write about the military, Afghanistan, its people, its culture and to do it in a truthful way. And in a comic way. In a way that hopefully was true enough that it didn’t destroy suspension of disbelief for anyone who had any knowledge of any of those three varied, deeply-felt experiences, let alone any combination of them.

I felt like I needed to try to absorb as much as I possibly could. I never had those experiences – Being an Afghan, being a female war correspondent, being in the military. I wanted to soak up as much as I could to get the courage to write in those voices. That meant reading a lot and meeting a lot of people. Talking to friends of mine in the military who were or are in Afghanistan, and friends of theirs. I met and talked to various Afghan nationals, writers and producers. I spoke with people at the State Department and NGOs. I tried to get it a little in my bones so that when people come back and say, “Well, it wouldn’t happen like that,” I didn’t feel too bad.

At our first meeting, she said, “This is your project now.” I had her permission to go write.

At a certain point, probably the twelfth time I wanted to meet with Kim and ask her something specific, she did say to me, “I think you’re over-reporting this.” That was helpful. I’d like to think she was probably saying, “You’ve asked the right questions. You’ve talked to the right people. Just go to it and quit mincing around.”

How different was writing WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT than writing for 30 ROCK or UNBREAKABLE KIMMY SCHMIDT?

The most obvious difference is that one is television. Writing serially is very collaborative. You’re producing so much material that, out of necessity, you have a staff. Deadlines come up so quickly that it’s important to have other eyes and other points of view on a day-to-day basis. That’s what a staff does. Writing a movie is a much more solitary endeavor.

In a serialized narrative, you’re telling stories at a different rate and in a different way. Whether it’s twenty-two episodes or thirteen, Tina and I always think about the whole season as an arc.

We start every season asking, “Where do we want to end up?” It is similar to thinking of the season as a very, very long movie, which is now possible for viewers who binge-watch. You also can step out of large narratives in serial storytelling. You can take diversions. You can correct course if something doesn’t turn out to be as compelling as you wanted it to be.

Telling a singular story is a very different thing. It meant sitting down and getting my head around what is the spine of this movie. What is this woman’s A to B to C?

What was the narrative theme you picked to highlight in WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT?

It’s about someone who has an opportunity to completely change her life and takes it. I think those are opportunities that don’t come all the time. Often when they do, people don’t have the courage – or perhaps moments of blissful stupidity – to seize them.

The consequences of that is what I found very interesting in Kim’s book. It was very compelling to explore where she ends up. That she knows that this new life she’s chosen – even for all the good it’s done her – is something that she needs to recover from. That takes strength as well.

I wish I had a pithier description of that. It’s a personal journey that could fit into a rom-com or [the Reese Witherspoon starring] WILD. The spine of WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT is that the world we’re living in, literally, is death, and absurd comedy is right outside the door.

One of the things I found in the film was the exploration of personal boundaries. It’s a different kind of performance than viewers have ever seen from Tina Fey. It’s also one of her finest acting performances.

Yeah, she’s great in it.

Tina’s character challenges herself to always exceed her own boundaries or how far she is willing to push her boundaries.

It doesn’t stop when you make that first leap. Part of what I found interesting was that it’s still your job. You build your friends, colleagues and co-workers. All of the mundane stuff still happens. You still have to think about people’s feelings, or not. You still have to make choices about what kinds of relationships you’re going to have. You still have to worry about work politics. You’re constantly being offered opportunities to make really bad mistakes. If they don’t go badly, you could continue an amazing adventure. If they do go badly, really bad things happen. People die.

There’s this seduction of both the adrenaline and the justified sense of one’s importance in the world and maintaining that. I’ve already used the word seductive, but it’s something that people have a hard time quitting. As Fahim says in the movie, it’s addicting and the addict always needs more and more. That’s when you get closer and closer to bad things happening.

What kind of environment do you like to be in when you write?

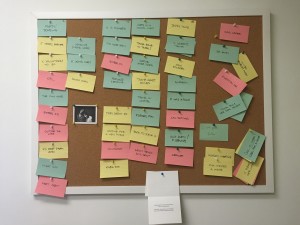

Tina and I have an office around Columbus Circle, which is far too noisy. In fact, the cards are still up on the board from WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT. Guess I need to take those down at some point. You can see on the right-hand side, beside a picture of Tina and Tracy Morgan taken at the very first 30 ROCK publicity shoot, that there are about one, two, three, four, five … Oh, my God. Probably twenty cards that fell out my first draft. My first draft was around two-hundred and seventy pages. About twice as long as it should be. That’s okay.

Tina and I have an office around Columbus Circle, which is far too noisy. In fact, the cards are still up on the board from WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT. Guess I need to take those down at some point. You can see on the right-hand side, beside a picture of Tina and Tracy Morgan taken at the very first 30 ROCK publicity shoot, that there are about one, two, three, four, five … Oh, my God. Probably twenty cards that fell out my first draft. My first draft was around two-hundred and seventy pages. About twice as long as it should be. That’s okay.

I like quiet when I write. I do like to be able to let my mind wander a bit. What’s nice is to stand up and go down the hall and talk to Tina or Eric Gurien. We have an extra office here and other writers’ friends will come and use the space. Tina’s husband has an office here and he’s working on a musical. He’s a musician and I can sometimes hear piano playing down the hall. I like to be able to choose my stimuli, either close the door or wander around and experience stuff.

My writing tends to come in waves. I have a very productive couple hours and then I need to recognize when I’m grinding. I have to push through that. That’s why I need a staff. The luxury with this is being able to go walk in the park for a minute, or go home and get drunk.

Is there a particular scene in WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT that you felt really translated well from the page to the screen?

Let me look at the board here. So much of what you end up doing as a writer – this isn’t exactly answering your question, but I will answer your question shortly – is imagining who is going to take your amazing, perfect words and direct it. You cast it in your head. I knew Tina, of course, but to then have Margot Robbie, Martin Freeman, Billy Bob Thornton, Chris Abbott and Alfred Molina. What they bring to the roles is already as much as you could imagine, in terms of translating it to the screen.

In terms of specific scenes, the reason I think of the actors first is because I’m thinking of the scenes with [high-level Afghan official] Ali Massoud Sadiq, Alfred Molina’s character. Those scenes are so dependent on this guy having a combination of charm, menace and a bit of sexual predation. You could imagine it being too scary or too silly and not so real. I love those scenes where there’s a lot that’s not being said. We writers require actors and it’s good to have great ones.

Can you tell me a piece of dialogue from WHISKEY TANGO FOXTROT that you really love and why?

There’s a moment after Kim is able to help General Hollanek. He is seeing Kim in a new light and she’s seeing him in a new light. It’s this moment where their avuncular friendship sort of coalesces. He says to her, “You ever feel like you’re working in a toll booth, and the engineer’s yelling, “I got pigiron. I got pigiron.” That is something my father-in-law likes to say whenever he gets a trick shot in tennis or squash when I play him.

Kim’s response is, “I don’t know what that means, but it sounds very folksy.” Kim is teasing him and he’s taking it, mostly knowing there are bigger fish to fry.

I wanted Hollanek to like Kim and vice versa. They start as oppositions, only to find value as people in the same circumstances. I knew that moment needed to work and I couldn’t ask for two better actors to play someone who quotes the song “Rock Island Line” and someone else who says, “That’s very folksy.”