Transcript

Speaker 1: Hello, you’re listening to OnWriting a podcast from the Writer’s Guild of America East. In each episode, you’ll hear from the writers of your favorite films and television series. They’ll take you behind the scenes, go deep into the writing and production process, and explain how they got their project from the page to the screen.

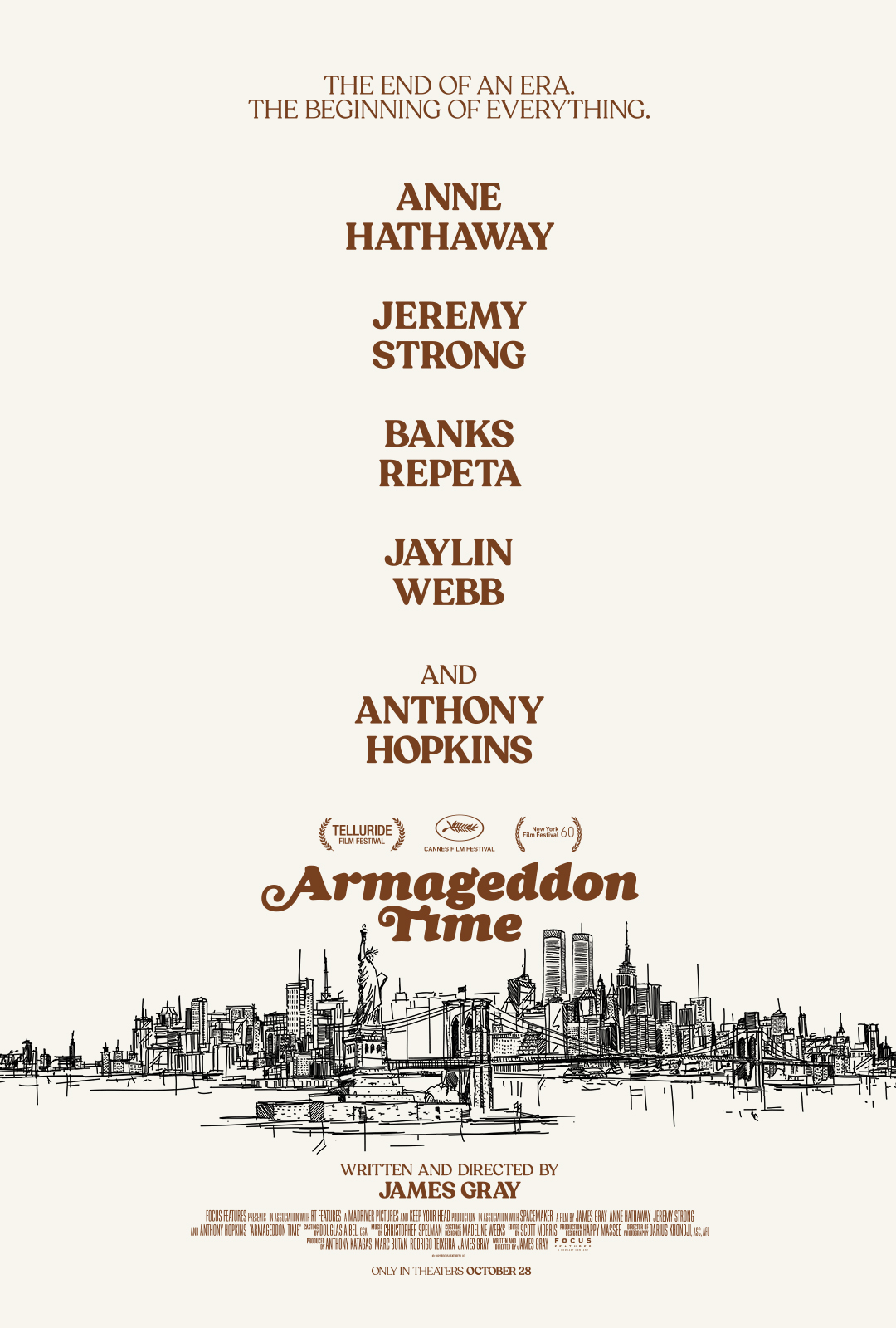

Alison Herman: You’re listening to OnWriting a podcast of the Writer’s Guild of America East. My name is Alison Herman. I’m a staff writer at The Ringer and a member of the Guild. And today I’ll be speaking with James Gray, the writer and director of the new movie, Armageddon Time. In our conversation, we touch on Gray’s upbringing as a secular Jew in Queens, attempting to empathize with Maryanne Trump, who he once encountered in real life as a middle schooler and the purpose of art and encouraging empathy across class and racial lines. I hope you’ll give it a listen. Our guest today is the writer and director of eight feature films, beginning with his debut, Little Odessa in 1994, most recently he directed Brad Pitt in the space drama, Ad Astra. For his latest project, he returns to New York and more specifically Queens for an intimate portrait of social class, assimilation and coming of age. I’m absolutely delighted to be speaking with James Gray. James, thank you so much for joining us.

James Gray: It’s great to be here. Thank you for having me.

Alison Herman: Of course. Well, this film Dramatizes a real incident from your childhood and we can maybe discuss what that incident specifically was. But my first question was if you always knew that you wanted to tell that particular story in the form of a film someday, or if that impulse arrived maybe more recently?

James Gray: No, I never actually thought of it as a film at all. It’s very hard to compartmentalize your life like that. Like you don’t say, “This is good for a film.” I never do that. What happens is that you begin to see, or at least in my case, I began to see what I thought were very specific and important currents in the culture that this particular series of incidents in my life had a kind of reflecting or rhyming quality with. So the whole idea was to make the film really to reflect and to resemble our world today. I found it at an uncanny kind of rhyme.

Alison Herman: Yeah, that’s a quality, I think, the film captures really well, that it’s very clearly from the perspective, not necessarily of a 12 year old boy in the moment, but of the adult version of that boy looking back on things.

James Gray: Well, a 12 year old boy, and in the case of both those kids, both the character that is a kind of stand-in for me in some respects, and also for Johnny, the character of Johnny, 12 year olds really don’t have all the tools, particularly 12 year old boys. It’s funny, I have two boys and a girl, three children, and my daughter has… I mean, how do I put this? Elegantly has matured emotionally on a significantly faster rate than my two boys. My daughter will be… She’ll be reading in the corner and my two sons will be hitting each other with clubs. And the reason I bring that up is that 12 year old boys, their brains are not yet developed to understand all of the specifics of moral and ethical questions and quandaries that we face.

And so in some sense, the film, yes, it is in the 12 year old boy point of view, and yet it’s not. How could it be? Because if it were, it would be a jumbled mess of cognitive dissonance, the story necessarily almost has to take a step away from that in order for it to make any sense at all. In that way, we have really no window into… Certainly into Johnny’s character for a variety of reasons and definitely… And not even mine.

Alison Herman: Well, speaking of having the window into Johnny’s character, that is a structural choice I wanted to ask about, that the film is largely, apart from a little bit towards the end, from Paul’s perspective, was the film always conceived that way, and why was that important to you in structuring the film?

James Gray: It was always conceived that way because it would be impossible. And you don’t just say this sort of thing to be sound hip or something. It’s an obvious fact of American life that there has been a very small, almost pinhole sized hole through which we see the world and there haven’t been a variety of voices telling their stories. So I felt that it was incumbent upon me only to try to tell my own, not to try to tell Johnny’s point of view because that would be insane.

I don’t have a window and didn’t actually have a complete window or even close to it of his life. So the only window I had that had specifics and accuracy to it was my own. But I feel that that’s okay. The idea is not to try to tell everybody’s story in one work. The point is to have a variety of voices, everybody telling their story, and that’s the richness of experience. So I felt that if Johnny’s story could be told, it should be and certainly not by me. So I tried to really focus it in on that perspective that I thought I had at least somewhat whole understanding of, and that is my own.

Alison Herman: That makes sense. I mean, you mentioned this sort of relative immaturity of a 12 year old boy and that perspectives and ability to totally understand the experience. So I’m curious what happened in the considerable amount of time between when this movie ends and when you started making it, when you started to form that understanding and what kind of things helped you in doing that?

James Gray: It’s a great question, but it’s not an easy one to answer because when you look at, dare I use this term history, it’s almost unknowable how many different factors enter in that change review of the world. I mean, the pandemic certainly did and does still with us. Trump’s election certainly did and does, economic disaster of 2008, certainly did and does, George Floyd certainly did and does. There are so many things that go into what makes up for a history and how history affects us and how we approach a piece of material, that it is almost unknowable. And trying to get to the core of it, it’s like trying to peel the layers of an onion. It is folly to do it, to try to analyze what has changed since 1980 that made you the person that you are that has affected your view of your own story, I just don’t have…

It’s a great question you ask. I’m not pooh-poohing it, but it’s impossible for me to have the distance necessary to specify what exactly I went through. What I can say is that the governing principle that I had really as a creative person from the very beginning that has only become intensified over the decades is that our function is to make sure that the long arm of compassion is lengthened ever further. And that the idea of ironic distance or making fun of a character or villainizing or demonizing, these are notions that we have to push away and to try and invite souls in to try and extend the reach of our understanding and our sympathy and our empathy.

That is to me, what art actually does. It’s not necessarily about seeing a reflection of myself, I give you me in the work, but it’s not only for you to see a reflection of yourself, it’s a reflection for you to have a window into somebody else’s world because that is how compassion is formed. So that is the one constant that I’ve had from beginning to end. And if anything, I believe in it more than I did 30 years ago.

Alison Herman: The film is incredibly compassionate, but I would say it also has some antagonistic figures chiefly the figures of Fred and Maryanne Trump, which I know is based on your own experience and on this theme kind of synthesizing your own memories into more of a concrete thesis. I’m curious what your initial instinctive reaction to those people was in the moment and when you started to connect the dots to their impact on the real world.

James Gray: Well, I have less, I don’t even know if I want to call it sympathy, but I have less understanding for Fred Trump than in a way that I do for Maryanne Trump. She came to the school and she gave a speech about how hard she had to work to get where she wanted to be. And I can tell you, even as a 12 year old, I found the speech completely preposterous. Ann Richards, former governor of Texas, she said about George W. Bush, I believe in 2000 in the Democratic Convention. She said, “George W. Bush born on third base and thought he hit a triple.” But it’s one thing to make fun of that and there is value to making fun of it, but it’s also worth our understanding that we are all each in our little individual ideological box. And it is unbelievably difficult for us to step outside of that box and look at another and see the world from another person’s point of view.

That’s why I get back to this idea of what art actually should mean and should help us do. And in her case, she was giving a speech as a woman, she felt, I guess the word would be oppressed, which seems insane to me, but that was the way that she felt. That was her box. She couldn’t see outside of it to see how absurd she was. You ever write an email, forget to send it, and then two weeks later you read what you wrote and all of a sudden you have some distance from what it is you created. And it seems an almost obscenely naive document. Well, it’s almost like that’s the kind of extended view of the world that I have, that everybody is constantly in their own heads and it’s our job to see past that.

So I look at her now, I don’t want to say with compassion, but I look at her now and I think I kind of see, well, she didn’t have a view of the world that was at all expansive. Is it her fault? Yeah, but where else could she be? Look at who her father is, look at the world she grew up in. She was cosseted. So my reaction to her then, is different than it is now. With Fred, I have less of a sympathetic reaction because frankly he had this one moment of confrontation with me in the hallway where he seemed like some kind of evil clown, and I couldn’t really formulate much of a more complex reaction than that. He seemed overtly antisemitic to me. But what do I know?

Alison Herman: I mean, it sounds like your read on Maryanne almost resonates with other themes in the movie and that it’s possible to experience oppression, whether it’s misogyny in her case or antisemitism in Paul’s, and not necessarily come away with the right lessons or experiencing it as a nobling event.

James Gray: A hundred percent. See, part of the problem is that when you provide a story like this, you have to remind… You find yourself reminding not just yourself, but sometimes frankly others, that it is not a purely simple divide between good guys and bad guys. And there’s all this discussion these days about things like white guilt and so forth, but it’s unfortunately more complex than that because it’s connected to the idea… This idea of privilege is connected with our economic system and frankly, the kind of ridiculous hierarchy that gets established because of class and race of course, but also yes, religion and gender and sexual preference, all that stuff seems to be like a hierarchy of unending complexity and it’s not so easily unpacked. So when we talk about these things, the idea is to show the world in all of its layers and all of its anguish on these layers so that we can understand that this is not simply something for a few buzz words or for a tweet, but for discussion.

Alison Herman: Yeah. So much with the way the movie approaches that idea is specifically through Jewish identity, in the way Jewish identity kind of confounds a lot of those binaries of privilege or not, marginalized or not. And given this movie’s roots in your own experience, I was curious about how you felt about an experienced Judaism as a kid, because it’s not really depicted as religious ritual in the movie. It’s much more of a cultural identity.

James Gray: Exactly. We were kind of what you might call secular Jews. I mean, it’s sort of like when people forget about the foundation of Israel was… David Ben-Gurion himself felt that if an Arab should win the popular vote, then so be it. The whole idea of the Kibbutz itself is almost kind of communist idea. It was not really a religious state in that sense. And my family was very secular. We did not really go to Temple and we were not observant in that way. But you cannot avoid the, as Ashkenazi Jews, you cannot avoid this sort of sway of Eastern European culture. So we had that, but you’re right, as a kid, I got that, well, I’ll call that cognitive dissonance where we’re oppressed but we’re not really, because there’s Johnny and look at him in the school and then look at me and I’m in a different… Really, I regard it differently, but at the same time, my parents are telling me to watch out because everybody hates us. This is why it is not digestible in a very simple slogan. It requires a kind of, that’s why I say it requires discourse and there are no “lessons learned” and there isn’t an answer provided by the film. There are only these questions.

Alison Herman: Given that this is the Writer’s Guild podcast, I did want to ask a few questions about your writing process. I read previously that you tend to have a longer outlining phase and a relatively quick screenwriting phase. Was that also the case for Armageddon Time?

James Gray: It’s always the case. If I find myself hung up in the writing phase, it means I haven’t done the work on outlining. It means something is wrong in the conception or the execution of the story or there’s something structurally wrong. I will tell you that I don’t know if I’m particularly categorizable as a good screenwriter, but I will tell you that I have gotten pretty good at outlining to the point where my outline determines the writing of it. And in the writing process, my first draft almost always winds up around 105 to 120 pages, which frankly is kind of the length you want to be at if you’re doing a three act structure. Now, of course, not to get too inside baseball, but this is the Writer’s Guild.

Alison Herman: Exactly.

James Gray: If you were doing a five act structure film, for example, The Godfather or something, that’s three hours long, or if you were doing something for TV, six hours, whatever, they are different structures, different formats, different ideas. But for a narrative feature, it’s interesting, last night I saw a movie called Jeopardy with Barbara Stanwyck and Ralph Meeker directed by John Sturges. And it was a quite good story idea, very effective story idea, kind of a Benoir and there was a lot I really liked about the movie. The movie was a hundred, no, it was one hour and seven minutes long. It was 67 minutes. And the movie had things that I didn’t think worked because they were not fully elaborated on or explored, but there was enough story there.

So you ask yourself, Well, why is that? Is that just my instinct, how I was raised? Well, no, there were certain things in the story that weren’t quite clear that they needed more time to explain. So if the movie were 90 minutes, 95 minutes, it probably would’ve been categorizable as a great movie instead of a merely very interesting one. So for whatever reason, our brains evolved and the movie going experience evolved somewhere around 1928, 29 to absorbing something around 90 to 120 minutes for three acts. And my outlines tend to run about, in screenplay form when I execute them, about that length. They are very detailed. They’re about 50 or 60 pages and they take months. But the writing process is usually only about two to three weeks for a first draft, of course I’m talking.

Alison Herman: Yes, of course. Chronologically, I’m curious how that outlining and writing phase lined up with your other work. Were you doing this while you were working on Ad Astra, or was this purely afterward?

James Gray: I have many friends who are in the motion picture business and many screenwriting, directing friends, many great ones. And I’ve noticed with tremendous admiration their ability to work on multiple projects at the same time or put something away and then revisit it. I am singularly inept at many things, not least of which is multitasking. When I was working on AD Astra, it was only that. And then there was only this. And I have never been able to change that, which is why I have… I’ve made eight pictures and I feel very fortunate. So don’t get me wrong, but I’m probably about two or three pictures behind the other directors I grew up with in terms of output because of this very reason.

Alison Herman: Well, that’s the wonderful thing about something like writing, because it’s so individual, everyone does it differently.

James Gray: That’s one of the beautiful things. As a friend of mine who’s a wonderful painter, he says, “The thing that’s magical about it is you don’t have to choose.” As a joke I’ll send him texts, I’ll say, “Chaïm Soutine or Francis Bacon?” And he’ll write back, “Neither And both.” Like the idea that you don’t have to choose, thank heavens. There is no one process. There is no one great way to do things. There is no one style that fits. It’s the universe that can accommodate 2001 and it happened one night and both are masterpieces.

Alison Herman: Yes, of course. I mean, you are in the very, I think, increasingly unique position of having written or co-written, I believe everything you’ve directed. And I did want to ask how those two identities of writer and director interact with each other and shape each process for you.

James Gray: I don’t really honestly see a path to directing without having at least some hand in the writing. But we really always was thus, even with the studio directors, I mean Alfred Hitchcock, I know that Vertigo is credited to other writers, for example, but he was such a integral part of the screenplay writing on all of his movies. He just didn’t take credit for it. So he was less pompous than we are, less obnoxious. The movie is the script. I mean, the screenwriting is everything. And let’s say you are working on a personal film, or a film that’s not autobiographical, but personal anyway, how else would you express that? It’s not only in where the camera goes, you know what I’m saying?

Alison Herman: Yes. Well, you’re also a visual artist by background as well, which is something that appears on screen in again in time. And I did want to ask, in addition to your identity as a writer, how your identity as a visual artist has translated into your filmmaking career?

James Gray: Well, it’s not that easy for me to talk about that because I did it. You know what I mean? I don’t really have the distance to say, I will tell you that I use painters as probably now, my principle inspiration for the work between my cinematographer and me. It used to be movies, movies and painting, other movies, and now it’s become restricted to painting. I mean, we looked at nothing for this one. I did show him lots of painters though, Darius. And so the composition and the light is certainly from that. But also I do write a lot of that stuff in. See, lighting has a huge impact on narrative and our perception of performance. For example, if you were to see the opening shot of Raging Bull, for example, which is one of the most famous openings ever, slow motion shot of him in the fog and the symmetrical boxing ropes and the opera music, if you were to see him clearly, his face clearly, the shot would have a very different meaning than it is now where he’s obscured in the robe, it becomes more of a mythic figure than otherwise.

So do you write that into the script? Well, I do because I feel like that’s part of the idea of creating this myth of character. So I write very… Sometimes quite irritatingly, I bet. I write very specifically all of these things. Now, Stanley Kubrick, if you were to ever to see the way that he wrote his scripts, for example, now there is an absolute master of cinema that we all look up to and rightfully so, but you read his scripts and they’re very strange. The margins are almost the opposite of our traditional writer margins. The dialogue is a smaller margin of… Kubrick’s dialogue is the larger one. It’s almost written like a play, but not really. And he has none of this stuff. But that was because his process as a director was on set to… He had at the time. He created a system where he had the time and he would figure it all out on the day. So I can’t work that way because my budgets aren’t that way. We can’t negotiate crew deals that way. It has to all be figured out in advance. That’s why we’re facing this new scenario. So I try to write those details in.

Alison Herman: Who are some of the painters that you’ve looked to for influences on past works, if not this one?

James Gray: It changes every movie. I mean, on this movie we looked at Zurbarán, who’s a fantastic painter. And it was weird too, also, because I don’t know what Darius Khondji, the cinematographer, I don’t know what he’ll always gravitate towards. So what I always do with him is we go to a museum wherever we’re shooting, we go to the nearest art museum and preferably one with a large swath of artists and types, variety being the spice of life. By the way, yet another riff on why you need to hear from more voices and all these different media. And for painting, we look at everything as varied from Van Gogh to Rembrandt and to Goya and all of a sudden to Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock and even I’ll say, “Hey, what do you think of Lee Bontecou, it’s random in a way. And then we begin to drill down.

On this movie, we went to The Metropolitan, which is a fantastic choice because unlike Laufer or The Prado, as great as they are, you go there for very specific types of art. And The Met has a very, very wide range. So in the same day, like I said, we were looking at Vermeer and the next minute we were looking at Adolph Gottlieb, just totally different form. So I think he gravitated towards one painting in particular on this movie, because I told him, I said, “I wanted the film to be a ghost story.” So the whole idea was that the actor was never truly in their key light. It’s a little bit unorthodox. If you’re lighting particularly a movie star, you always put the key light on in a way that’s very flattering and so forth. But here, for example, the kid comes home from school and Anne Hathaway’s in the living room, but the light is coming from the dining room and she’s not quite in the key light, so everyone is like a ghost story.

Everybody’s avoiding the light. Everybody is slightly elusive to us, visually. So even in the dining room scene when they’re having dinner, there’s a top light chandelier, but it’s two stops underexposed. In other words, everything is sort of like these people are temporary inhabitants of the space. And he gravitated towards a painting by Vermeer, which was of a maid sitting in the kitchen sort of like this. But the key light being quite a bit in the foreground. And she’s in the back sort of, like we would say in photography, maybe three stops underexposed.

Alison Herman: I wonder if the idea that this is a ghost story is related to one of my takeaways from the film, and I think one that is specifically a product of your collaboration with Darius Khondji is that it is a film that really feels very viscerally like a memory. It doesn’t really feel like you are experiencing 1980 necessarily in the moment as Paul is, but it feels like you are looking back on it almost as a remove. Was that part of what you were trying to get at with the ghost story conceit?

James Gray: A hundred percent. We change things in our memories completely. One of the strange things about photography is that, or cinema, is that it’s sort of the closest thing we have to a time machine. So I could remember a class photo one way and then find that class photo 30 or 40 years later, and it’s quite different than my memory was. And so knowing that that idea of memory, and I don’t want to call it nostalgia, because nostalgia is usually a positive glow on something, and I don’t think that that’s what this film is at all. But that distance that we create where our mind wreak havoc on what we might call objectivity, which of course is folly anyway, it requires a necessary visual distance. Now, let’s be very frank here, and it’s very important as a distinction, what is visually distant is not the same thing as emotionally distant.

An emotional intimacy and proximity is essential to a work of art. Visual distance is not the same thing. You almost need to have both, some measure of visual distance, but none of the emotional distance. So what we were trying to do was create this idea that the film is this memory, this reaching back in time that these people who were so important to me, my mother, and sadly now my father and my grandparents, my great aunt, my grand, they’re all dead. They’re all gone. And their memories are… It’s only up here. That’s it. Dancing around in my brain like little fireflies and the memory of them is getting a little dimmer. I have a great difficulty remembering my mother in a healthy state to be candid. So you present these things with love, but also with distance, not with judgment, but distance.